Running a Charity:

Working with Other Organisations

See also: Careers in the Third Sector

Charities do not operate in isolation. There may be times when they want to work with another charity, for example, to share a fundraising platform or facilities, or put on a joint event. They may also choose or need to work with a non-charitable organisation. This will include commercial fundraising organisations, trading subsidiaries of the charity itself, and grant-making bodies.

Charity trustees or directors need to consider carefully before they establish a relationship with any other organisation. They must be sure that the relationship is in the charity’s best interest, and that it represents the best way to achieve the charity’s aims. There are also different considerations when the organisation is a charity, and when it is not. This page explains some of these issues.

Working with Other Charities

The simplest organisational relationship for charities is with other charities.

Government guidance in the UK is very clear: charities can work together to deliver their purposes.

This might include, for example, providing joint training courses for employees or volunteers, or sharing office or other space to save on overheads. Sharing knowledge and skills may also be important. Charities can also work together to give themselves a better chance of getting a contract to provide services, or to provide funding for another organisation if that best delivers their purposes.

Before embarking on any joint working, it is therefore important that the trustees or directors of both charities have considered why they might work together.

They also need to be confident that the relationship is in both charities’ best interests, and that this is an effective way of using resources to deliver the charity’s purpose. It follows that joint working must not be prohibited by either charity’s governing document. Finally, trustees need to be confident that they have identified and are managing any risks that may occur (and for more about this, you may like to read our page on Risk Management).

It is particularly important that you are clear that working with another charity will not affect the support that you already receive. For example, it should not dissuade existing donors from continuing to support you.

Finding another charity

How do you set about finding another charity with which to work?

It depends why you want a partnership.

If all you want is to share a working space, you may just want to look for another charity of any kind in your area. If you want to share other resources, or bid for a project, then you will need to look for another charity that has a similar or complementary purpose. If you have a similar target audience, you might want to fundraise in partnership to save resources.

For example:

- It can work well for youth charities to work together to deliver safeguarding courses to their volunteers, because they share similar aims, and need to provide similar information. Other charities may not have the same need to train their volunteers.

- Two local hospices may find it more cost-effective to put on joint fundraising events than to work separately. They are probably already splitting the local donations, and could both put less resource into a joint event.

- Two charities with very different purposes might also work together to raise funds. If their likely audience is very different, this could introduce new supporters to both. However, they may find it hard to agree what event to run if they are targeting different groups.

Establishing a working relationship

Once you have found another charity with which to work, you need to establish how you will work together. You will eventually need a formal written agreement—but you also both need to be clear about what you each want individually before you start negotiating. In particular:

How will you remain independent? For example, will you put together a shared team for your joint purposes, and keep other staff separate?

How compatible is the way that you work? Even if your purposes are very similar, are your operations comparable?

What will each charity be responsible for? What is your ideal position on this, and how far are you prepared to compromise?

Horses for courses

The nature of your written agreement will depend on the complexity of your relationship. A more complex relationship will naturally require a more complete agreement, including termination clauses.

Working with Non-Charities

Charities may also work together with organisations that are not charities. This includes the situation where the charity:

Has set up a trading subsidiary;

Has been set up by another organisation, such as a social enterprise or government body;

Gets regular funding or support from another organisation;

Gives regular support or funding to another organisation, for example, if a grant-making body is a charity, or if a charity is set up to raise funds for a hospital or school;

Works regularly with another organisation, for example to deliver services or campaigns;

Has another organisation as a trustee, or another organisation can appoint trustees of the charity; and

Has another organisation as its only member, or one of its most important members.

The ‘other organisation’ in each case may be privately-owned, a government agency or body, or a not-for-profit organisation. The key is that it is NOT a charity.

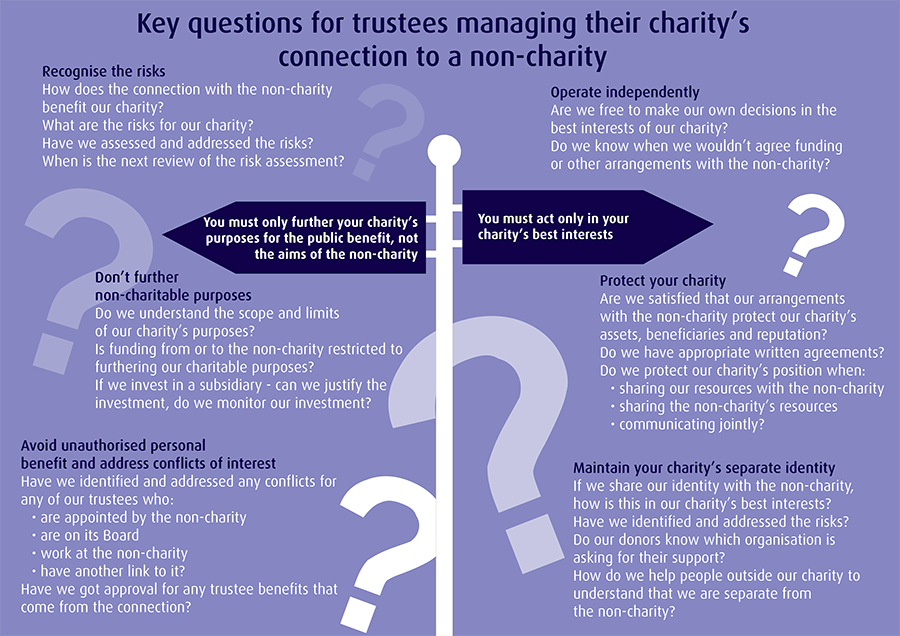

Charity regulators may set out rules or a framework for how non-charities and charities should work together. For example, the Charity Commission for England and Wales has set out six principles for charities working with non-charities (see box). These do not apply elsewhere—but they may be a good starting point for charity trustees or directors. You should also check guidance from your own regulator.

Six principles for charities working with non-charities

Recognise the risks, and ensure that you review them regularly, and manage them effectively.

Do not further non-charitable purposes. For example, you need to be aware of the limits of your shared purposes, remembering that non-charities do not need to operate within charitable purposes. They may also operate to make a profit, or to do other things.

Operate independently of the other organisation. This means that the charity remains governed by its trustees, working in the charity’s best interests. It must also exist only to deliver its charitable aims in the public interest. This is especially important for charities set up by non-charities, and dependent on them for funding.

Avoid unauthorised personal benefit and avoid conflicts of interest. This might arise, for example, where a family member or friend of a trustee or employee is involved in the other organisation, or where a trustee or charity employee might benefit directly from the arrangement.

Maintain the charity’s separate identity, by keeping separate financial and legal identities and accounts.

Protect your charity, including its assets, reputation and beneficiaries. This might mean considering alternative ways to deliver your purposes. It will also include having written agreements for joint working and getting adequate information (carrying out due diligence) before making an agreement.

It follows that charities should always have a formal written agreement in place for any working arrangement with another organisation—and that this agreement should be consistent with their governing document.

There is a useful infographic for charity trustees to use when developing a relationship with a non-charity (see below).

What happens if something goes wrong?

Generally, regulators will expect charities to act promptly to put things right. This might include acting to minimise damage to the charity’s resources and reputation. It will also include ensuring that the situation does not happen again, for example, by stopping the arrangement, or resetting it by revisiting the formal agreement.

If ‘what goes wrong’ results in serious damage to the charity, the regulator may impose fines or penalties.

A Final Thought

As with any other action of a charity, trustees are liable for decisions about working with other organisations, both charities and non-charities.

There is always a possibility that something may go wrong, and if so, trustees will be responsible for putting it right. However, it is also true that if trustees act in good faith, in the best interests of their charity, and in line with guidance from their regulator, they should be reasonably confident in the outcomes.

Source:

Source: